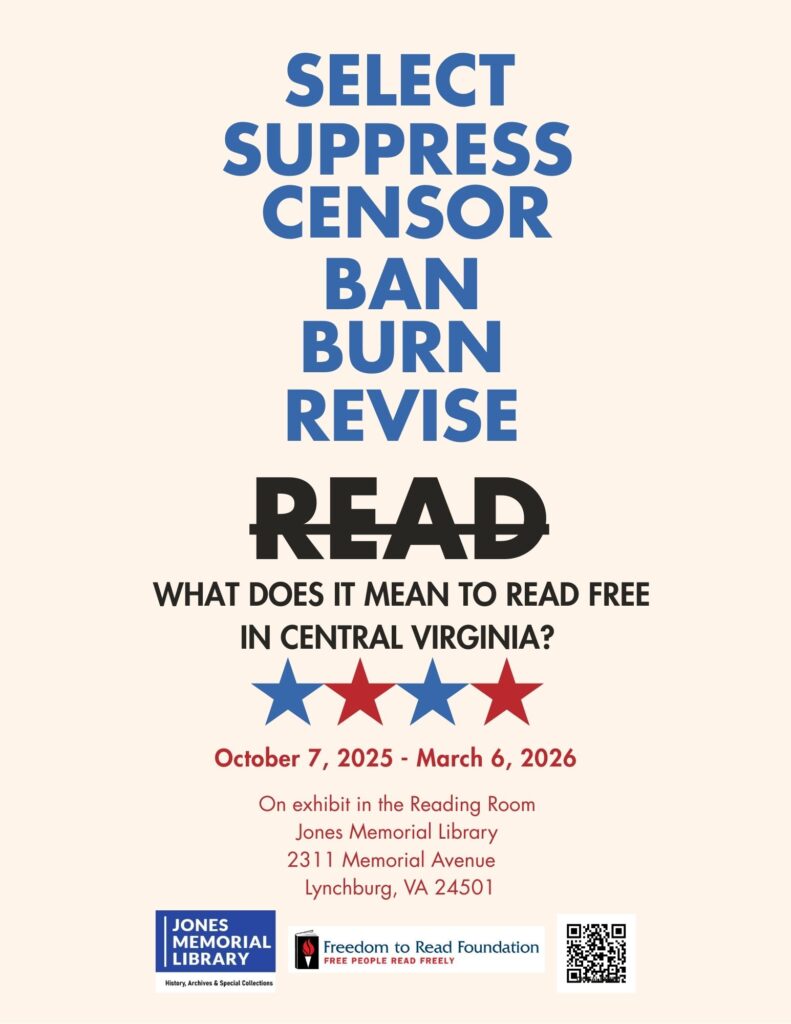

About READ

READ is an exhibit at Jones Memorial Library which shares a history of censorship efforts in Lynchburg and Central Virginia between 1660 and 1960. Using examples of actual historical events,

READ shares primary and secondary sources related to those events and covers examples of censorship on topics ranging from religion to abolition, and across formats including books, music, and film.

READ is on exhibit at Jones Memorial Library from October 07, 2025 through March 06, 2026. The exhibit is free and open to the public. This page features images and content from the physical exhibit. Click on an image to see the related item in our Digital Collections.

READ has been made possible with grant funding from the Freedom to Read Foundation and a 2025 Phyllis Krug Banned Books Week Programming Grant. Jones Memorial Library is grateful for this funding and the opportunity to share these historic resources with the community.

Exhibit Panels

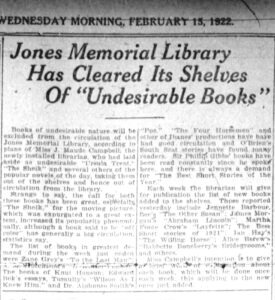

Maud Campbell (above left) was JML’s Head Librarian from 1922 to 1947. In 1922, one of her first acts at Jones was to remove titles from the collection that she felt were ‘unsuitable’ for the reading public.

Thirty years later, in 1952, the Lynchburg newspaper reported that ‘racy’ publications were still popular in Lynchburg.

In 2025, JML restored reprints of two titles Campbell removed, “The Sheik” and “Ursuala Trent”, to its collection.

Professional librarians operate under the principle of selection rather than censorship, guided by their library’s policies and established criteria to build collections of merit that serve their entire communities. Collection management, or curation, involves ongoing professional decision-making. Weeding is the systematic removal of outdated, damaged, or rarely-used materials—it is essential to collection maintenance and differs from the removal of controversial materials based on content or ideological objections. The use of transparent policies and procedures, creating accountability and consistency in collection decisions is fundamentally different from censorship, which seeks to suppress ideas based on ideological objections rather than professional library standards.

In colonial Virginia, book selection was limited by economic factors and social hierarchies. The establishment of Virginia’s public education system in the 1870s introduced new selection dynamics. By the mid-20th century, professional librarian standards began influencing selection practices. The American Library Association developed intellectual freedom principles that challenged existing selection criteria, though Virginia communities sometimes resisted these changes. Central Virginia counties including Bedford and Henrico maintained selection policies that favored traditional literature and excluded works addressing certain topics including sexuality, racial inequality, or religious diversity.

Selection committees today navigate multiple pressures: professional standards calling for diverse, age-appropriate collections and community voices demanding adherence to specific moral frameworks. Jones Memorial Library’s own selection history demonstrates that collections can reflect a librarian’s particular values and perspectives. Patron requests for materials may influence selection and questions about whether multiple perspectives receive consideration in the decision-making are part of the process at most circulating libraries.

2. SUPPRESSION

The act of limiting or restricting access to information or ideas, which can include removing materials from public access or imposing barriers that prevent people from encountering certain content.

Comprehensive anti-Quaker statutes in the 1600s forbade the entry of Quakers into Virginia.

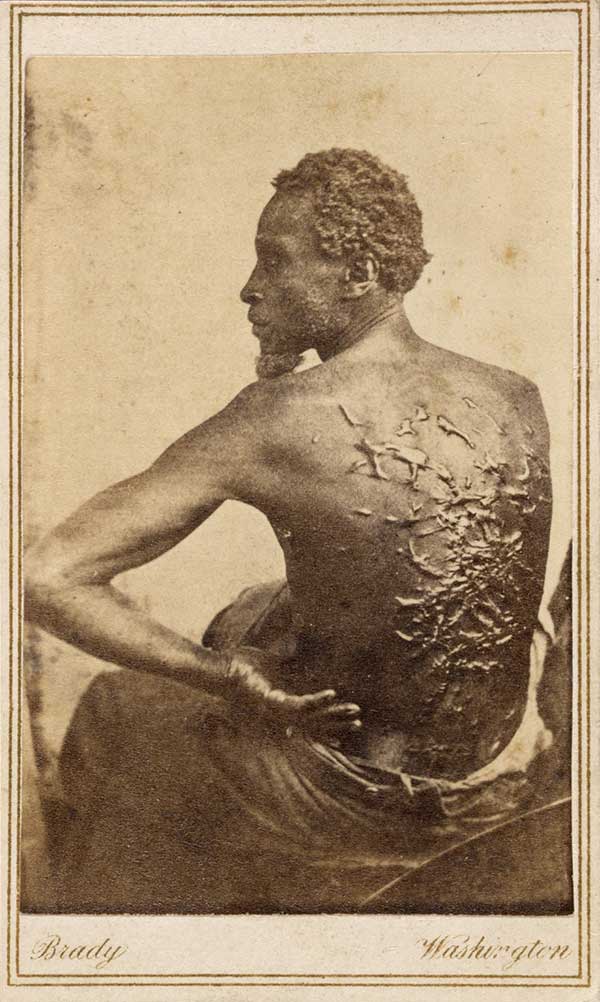

Photographs by Matthew Brady were often considered too graphic or shocking to be printed in newspapers at the time. Brady’s photographs were highly influential in shaping public opinion against slavery.

Far left: “Peter (formerly identified as Gordon)”

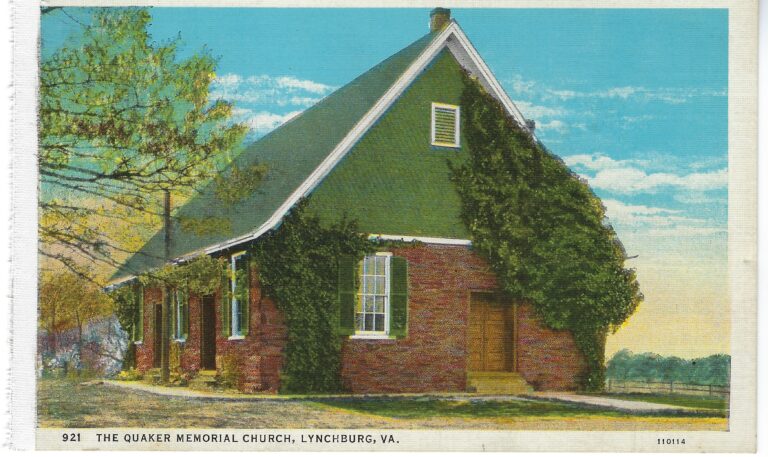

Right: Postcard circa 1900 of the Quaker Meeting House in Lynchburg, Virginia

Suppression of Quaker literature in colonial Virginia began with the first ban on books enacted in March 1660. The General Assembly and Governor Sir William Berkeley passed an ordinance against the Quakers which outlawed publication of their books, pamphlets, and other written works.

Comprehensive anti-Quaker statutes forbade any ship master from bringing members of this religious sect into the Virginia colony under heavy penalty. Laws required imprisonment of detected Quakers until they swore to leave and never return, and “rigidly proscribed” the circulation of their books and pamphlets. This literary suppression continued throughout the colonial period until the passage of the Act of Toleration by the British Parliament in 1688.

The suppression of the freedom to read in the pre-Civil War period represented one of the most systematic and severe restrictions on intellectual liberty. On April 7, 1831, just months before Nat Turner’s Rebellion in Southampton County, the Virginia General Assembly passed “An Act to amend the act concerning slaves, free negroes and mulattoes,” which declared that “all meetings of free negroes or mulattoes, at any school house, church, meeting-house or other place for teaching them reading or writing, either in the day or night, under whatsoever pretext, shall be considered as an unlawful assembly.” While Virginia never explicitly banned the education of enslaved people, it made such education practically impossible and extremely dangerous.

The campaign against dangerous reading materials extended beyond formal education to encompass censorship. Southern post offices became battlegrounds, with mobs seizing and burning abolitionist literature while states throughout the South reacted with legislation prohibiting circulation of abolitionist literature and forbidding enslaved persons to learn to read and write. The suppression of reading freedom in Virginia thus revealed both a recognition of literacy’s revolutionary potential and the indomitable human desire for knowledge that no law could fully extinguish.

CENSORSHIP

The act of some authority taking measures to suppress ideas and information within a book or other materials, typically motivated by moral, religious, or political objections to the content.

Censorship in Virginia has operated through both visible removals and quieter restrictions that limit intellectual access. Unlike outright banning, censorship has sometimes appeared as accommodation or as a protective measure.

Virginia’s censorship patterns have shown connections to periods of social concern. The 1925 Butler Act, while focused on evolution education, established precedent for content-based restrictions in Virginia schools. Literature classes began avoiding works that contradicted certain religious teachings, creating informal restrictions through institutional responses.

The Cold War era saw increased censorship efforts. Virginia libraries removed books considered sympathetic to communism, while schools avoided literature critiquing American foreign policy or economic systems. The 1954 massive resistance campaign against school integration in the South extended beyond racial policies to encompass restrictions on civil rights literature and progressive social critiques.

Jim Crow era practices represented systematic censorship through segregated access. Contemporary censorship takes various forms. Restricted access policies place controversial books in separate collections requiring special permission. Age-classification systems remove young adult literature from teen sections based on content concerns rather than developmental research. Digital filtering systems block online resources containing certain keywords, preventing students from accessing some academic content.

The distinction between age-appropriate guidance and censorship involves examining process and intent. Content curation may involve transparent criteria applied across ideological perspectives. Other approaches employ standards that target specific viewpoints while protecting opposing views, sometimes through procedures that challenge defenders rather than evaluate content systematically.

Virginia’s censorship developments show how restrictions may expand over time. Current limitations may become precedents for future restrictions.

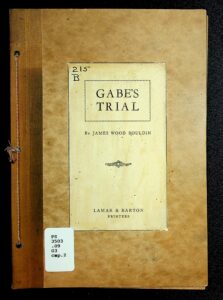

Evolution was a controversial concept in the 1800s. James Wood Boulding was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives between 1834-1839, during which he served on the Committee on the District of Columbia. Boulding opposed abolishing slavery in Washington D.C. “Gabe’s Trial” (above left) by Boulding is a fictional treatise against evolution, written in a stereotyped, black southern English style.

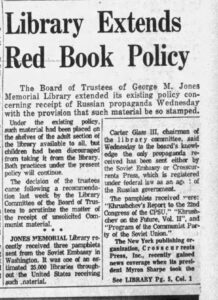

In the 1960s, public libraries across the United States received unsolicited political propaganda materials from the Soviet Embassy. At Jones Memorial Library in 1962, these materials about communism were made available to adults but children were officially discouraged from accessing them (above, right).

BANNING

The act of some authority taking measures to suppress ideas and information within a book or other materials, typically motivated by moral, religious, or political objections to the content.

Carousel above:

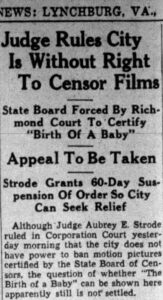

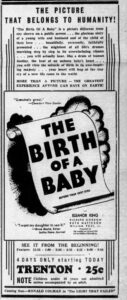

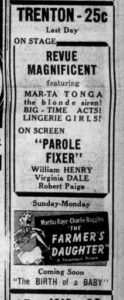

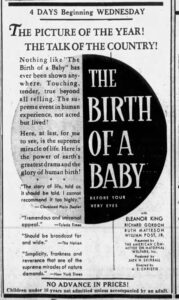

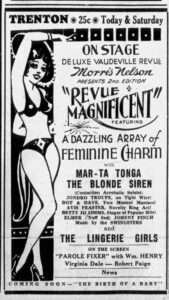

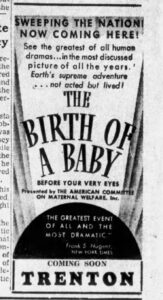

“Birth of a Baby” was an educational film about childbirth. Lynchburg’s Paramount Theater was a center of controversy in 1940 when the City Council attempted to prevent showing the documentary at the theater. The case went to Virginia’s highest court, which ruled that no city could ban films that had been approved by the State Board of Motion Picture Censorship. Birth of a Baby was later shown at the Trenton Theater in Lynchburg.

Book banning has represented censorship’s most visible form, transforming restrictions into public declarations about acceptable thought and expression. Virginia’s banning history has reflected cultural conflicts over race, sexuality, religion, and political ideology, with books serving as symbolic representations of competing social visions.

Virginia’s early book bans targeted religious dissent. Colonial authorities prohibited Quaker and Baptist texts that challenged Anglican Church orthodoxy. The Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom protected belief but did not extend these protections to written expression, allowing continued restrictions on religious literature.

The pre-Civil War period saw banning of abolitionist literature. Following Nat Turner’s 1831 rebellion, Virginia prohibited materials that questioned slavery or encouraged literacy among enslaved populations.

Reconstruction brought new banning targets. Virginia localities banned textbooks presenting certain views of federal intervention or equal rights amendments. Uncle Tom’s Cabin faced prohibition in many Virginia communities well into the 20th century, while pro-Confederate histories received different treatment. The 1970s saw significant textbook controversies in Central Virginia.

The Cold War era expanded banning rationales beyond morality to national security concerns. Virginia schools banned books critical of American capitalism or foreign policy, while libraries removed works by authors with suspected communist associations. The 1962 Supreme Court decision regarding school prayer coincided with increased Virginia book banning as communities sought to maintain religious influence through literature control.

Book banning represents community choices about intellectual development. Virginia’s history shows that banning practices have reflected power structures and particular values.

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” was published in 1852. Stowe’s work was so influential that Abraham Lincoln was said to refer to her as the ‘little woman who wrote the book that made this great war.’ Her book received much resistance and she was moved to share the factual basis of her work in “A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin”. Seth Woodroof, a Lynchburg slave trader, was mentioned in Stowe’s work. Jones Memorial Library has Woodroof’s slave trading account book from the 1830s in the collection.

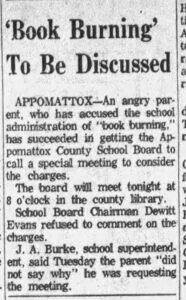

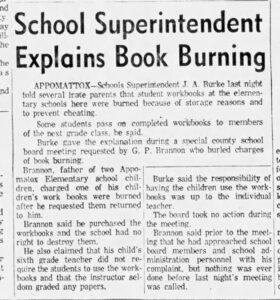

BURNING

The practice of physically burning and destroying books or other written material, usually carried out publicly and motivated by moral, religious, or political objections to the material with a desire to eliminate it.

Book burning transforms intellectual disagreement into physical destruction, representing rejection of alternative perspectives through elimination of their material existence.

In Virginia book burning began with colonial religious conflicts. Some Puritan communities burned Anglican texts, while Anglican authorities destroyed Quaker and Methodist writings.

The Civil War era saw systematic burning of educational materials. Union forces burned pro-slavery textbooks, while Confederate supporters destroyed Union-sympathetic and abolitionist literature. These book burnings targeted ideas as well as materials, attempting to erase the intellectual foundations of opposing ideologies.

Reconstruction brought vigilante book burnings by groups who burned schools and their libraries to prevent Black education. The 1873 burning of the Freedmen’s Bureau school in Norfolk destroyed hundreds of books specifically because they enabled Black literacy and political consciousness. These represented calculated attacks on intellectual development.

The early 20th century witnessed Virginia book burnings targeting evolutionary science and modern literature. The 1925 Scopes Trial inspired fundamentalist communities to burn textbooks containing evolutionary theory. Local revivals featured ceremonial burning of books deemed morally corrupting, including novels by authors such as Theodore Dreiser and Sinclair Lewis.

McCarthyism produced Virginia’s most systematic book destruction. The 1953 burning of library books in several Virginia counties eliminated works by suspected communist authors.

The civil rights era saw renewed book burning targeting integration literature. The 1962 burning of civil rights books at a Virginia Beach rally destroyed both printed matter and symbolic representations of racial equality.

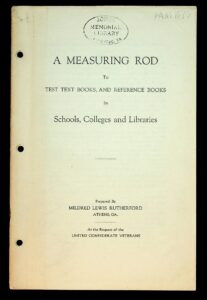

REVISION

The process of modifying or editing the content of books or materials to remove or alter passages deemed objectionable, often done to make content more acceptable to certain audiences, comply with censorship demands, or misrepresent historical events.

Revisionism represents intellectual control through alteration rather than elimination. Revisionist practices include rewriting historical narratives to serve contemporary needs. Revisionism involves maintaining authority while altering content. Unlike banning, which generates controversy, revision may be justified and appear as part of the normal editorial process.

Revisionist practices in Virginia emerged following the Civil War. The Lost Cause movement sought to transform Virginia’s defeat from one interpretation to another, rewriting slavery as a different kind of institution and secession as a constitutional principle. Textbooks like “A School History of the United States” (1896) described slavery and the deprivation of freedom for a large percentage of the population in often inaccurately rosy ways, while portraying Reconstruction as federal overreach.

Educational revisionism became systematic in early 20th-century Virginia. The United Daughters of the Confederacy successfully lobbied for textbook adoption committees, ensuring classroom materials promoted specific pre-Civil War narratives. Books describing slavery’s harsh realities were revised to emphasize positive master-slave relationships, while accounts of Black resistance disappeared from official histories.

Modern revisionism has operated through textual manipulation. Contemporary examples include editing American history textbooks to adjust slavery’s economic importance. Digital media has enabled new revisionist approaches. Online resources can be filtered to present selected information on controversial topics. Search restrictions may prevent students from accessing primary sources that contradict official narratives, while curated content can guide interpretation toward predetermined conclusions.

The effects of revisionism extend beyond historical accuracy. Virginia students studying revised materials may develop particular understandings of complex social issues, influencing critical thinking about contemporary problems rooted in historical patterns. Revisionist practices have shown that controlling interpretation can be more effective than controlling access. When communities cannot eliminate opposing perspectives entirely, they may seek to shape understanding through selective presentation and contextual manipulation, achieving ideological goals through apparent scholarly objectivity rather than more obvious censorship.

Recommended READing

Sources

- Black, Hillel. The American Schoolbook. New York: Morrow, 1967.

- Bruinius, Harry. Better for all the World : The Secret History of Forced Sterilization and America’s Quest for Racial Purity. New York: Vintage Books, 2007.

- Cox, Karen L. Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003.

- Curtis, Michaell Kent. “The Curious History of Attempts to Suppress Antislavery Speech, and Petition in 1835-37.” Northwestern University Law Review, 89, no.3. (1994-1995) 785-870.

- E.K. and S.K., minors, by and through their parent and next friend Lindsey Keeley, et al., v. Department of Defense Education Activity, et. al. 1:25-cv-637. (US District Ct for the Eastern Dist of VA, Alexandria Division. 2025

- Elson, Ruth Miller. Guardians of Tradition, American Schoolbooks of the Nineteenth Century. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1964.

- Early, Jubal Anderson. The Heritage of the South. Lynchburg, VA: Press of Brown-Morrison Co.,1915.

- George, Walter Lionel. Ursula Trent. London: Forgotten Books, 2016.

- Hull, E.M. The Sheik. London: Forgotten Books, 2016.

- Janney, Caroline E. Burying the Dead but Not the Past: Ladies’ Memorial Associations and the Lost Cause. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

- Jarvis, Zeke. Silenced in the Library: Banned Books in America. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2024.

- Kandiuk, Mary, ed. Archives and Special Collections as Sites of Contestation. London: Institute of Historical Research, 2020.

- Lee, Susan Pendleton. Lee’s Advanced School History of the United States. Richmond: B. F. Johnson Pub. Co., 1897.

- Munford, Beverley B. Virginia’s Attitude Toward Slavery and Secession. Richmond: L.H. Jenkins, 1909.

- Page, J. W. Uncle Robin. Richmond: J. W. Randolph, 1853.

- Page, Thomas Nelson. The Negro: The Southerner’s Problem. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1904.

- Page, Thomas Nelson. Robert E. Lee, Man and Soldier. New York: Scribner, 1929.

- Page, Thomas Nelson. Two Little Confederates. New York: C. Scribner’s, 1932.

- Pollard, Bill. The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates. New York: Bonanza Books, 1974.

- Reynolds, David S. Mightier than the Sword: Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the Battle for America. London: W.W. Norton, 2011.

- Rutherford, Mildred Lewis. The South in History and Literature. Atlanta, GA: Franklin-Turner Co., 1907.

- School History of the United States. Philadelphia: Eldredge & Brother, 1897.

- Stowe, Harriet Beecher. A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Boston: J.P. Jewett & Co., 1853.

- Summers, Robert E. Wartime Censorship of Press and Radio. New York: Wilson, 1942.

- Unknown. “Uncle Tom Without A Cabin.” Unpublished Manuscript, JML.MS1667, 1902.

- Williamson, Mary Lynn (Harrison). The Life of Gen. Thos. J. Jackson, “Stonewall,” for the Young. Richmond, Va.: B. F. Johnson Publishing Co., 1899.

- Williamson, Mary Lynn (Harrison). The Life of Gen. Robert E. Lee, for Children, in Easy Words. Richmond, Va.: B. F. Johnson Publishing Co., 1895.

- Williamson, Mary Lynn (Harrison). The Life of J. E. B. Stuart. Atlanta [etc.]: B. F. Johnson Publishing Co., 1914.

- Wilson, Charles Reagan. Baptized in Blood: The Religion of the Lost Cause, 1865-1920. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1980.

Credits

READ has been funded by a 2025 Judith F. Krug Memorial Fund Banned Books Week Programming Grant awarded by the Freedom to Read Foundation. For more information on the Judith F. Krug grant program and the Freedom to Read Foundation’s work and mission visit www.ftrf.org.

Exhibit Curation: Molly Landergan, Deborah Smith

Panel Design: Molly Landergan

Research Support: Gwen Wells, K.H. Woodford, Nancy Weiland

Digitization: Garrett Reynolds

Exhibit Advisors: Lisa Broughman, Carolyn Sherayko

Some narrative text and research assisted by Claude A.I.

A digital version of this exhibit is available online at www.jmlibrary.org/digital-exhibit/

Visit our Exhibit item set of related historical materials on Omeka-S.

All exhibit text and materials copyrighted by the George M. Jones Library Association, 2025.